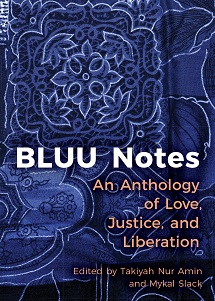

Book cover is copyrighted material used for illustrative purposes.

Book Review – BLUU Notes: An Anthology of Love, Justice and Liberation edited by Mykal Slack and Takiyah Nur Amin

In the tradition of Been in the Storm So Long and Voices from the Margins, the meditation manual BLUU Notes: An Anthology of Love, Justice and Liberation joins the legacy of treasures generated by Skinner House Books. Created and birthed through the collaborative efforts of Takiyah Nur Amin and Mykal Slack, the anthology’s themes of love, justice and liberation are captured in the creative talents of its contributors, whose voices are massaged and birthed through their tears, pain, laughter, joy and sheer determination.

This small meditation manual is overflowing with the soulful Black voices of familiar and new talent. Twenty individuals serenade the readers with their poetic poise, accompanied by six songs reflecting a beautiful blending of musical lyrics. Musicians, Mykal Slack, Glen Thomas Rideout, Ysaye M. Barnwell and Reverend Osgyefo Sekou are familiar names and treasures in Unitarian Universalist circles. David Frazier’s name is perhaps less known, but familiar because of his widely popular song, “I Need You to Survive.” His is a name now engraved on my heart. Melanie DeMore’s “Hold Everybody Up” is a new name to me that I look forward to hearing more from in the future.

If the music is on point, the poetry is magical, hard hitting, poignant and memorable. Morning Song by Patrice Curtis reminds us that we are, “the spirit of the holy, face of the sacred, strong, the universe manifest.” Mykal Slack’s Prayer of Power and Wonder recalls BLUU’s 2019 Harper-Jordan Memorial Symposium, when he lifted up the participants with this prayer. He reminds us that our coming together invites laughter, crying, breaking bread, cutting up, learning and growing together. Viola Abbitt’s prayer, Toward a Place of Wholeness, encourages us to look beyond the places Unitarian Universalism (UU) has fallen short. And that it has, “shifted course to move toward a place of wholeness; a place that has perhaps never existed for us…”

Soren Byrd, AKA Benita Jeanelle, speaks lovingly in the poem, Digital Faith, about the lit chalice that “turns on the light in our souls.” One of our UU elders, William G. Sinkford, inspires us in a prayer titled, Only Begun, to “imagine justice and mercy…hold fast to our vision…see hope in our history…find courage…work for constant rebirth.” Melissa C. Jeter challenges us with Black Girl Blues, reminding us that our ancestors paid the dues for us. Charlene Carruthers’ poem, Radical Imagination, proclaims we were “made for this moment…for future generations…they have called us to this moment.” Mallessa James’ poem, Dark Natured, plays with images of darkness, symbolizing the womb, soil, our bodies, minds, monsters and secrets.

Jan Carpenter Tucker, in Sankofa–Go Back and Get It, suggests we fetch what is at risk of being left behind and … “see what we can do differently.” Sherryl N. Weston proclaims her love for UUism in her poem, Finding Our Way, and what it has done for her spiritual journey and UUism’s openness to many religions. Mya Wade-Harper announces, “I am here to stay” in her poem, Being UU and Black. Our beloved ancestar Mathew P. Taylor’s Lamentations extolls lamentations as a way to be “seen, held, heard…so that the weeping stories are not silenced.”

Anthony Y. Stringer, another UU elder, captures the meaning of the African Spirit, in his poem of the same name. The African Spirit provokes him to be mindful, reverent, humble, grateful, in service, and creative. He reminds us that Spirit is available in each of us. Sofia Betancourt dedicates her poem, Gather the Bones “for the ancestors whose funeral prayers I sang under the full moon that night in Cuba.” She reminds us that “our history lies in those bones… the tortured voices” and so we are inspired to gather the bones.

Everett Hoagland, another of our elders, echoes the protest chant, “No Justice No Peace” in his poem, The Music. He recalls that the words and sentiments are no longer solely embraced by Blacks but “with masses of allies… as we trod the stony road…we have always been on.” Ebony C. Peace’s Lynching Version 2 compares the “knee on her neck a modern noose,” and invites us to reflect on similarities between past and present forms of oppression. Elias Ortega’s On Blue Notes and Resolutions utilizes Black music to expose the reader to the deep suffering portrayed in the blues, as well as the importance of resolution as a way forward.

Finally, my short poem titled, God Knows My Name grew out of my understanding of what it feels like to have constant communion with the Most High – the Holy. And because of that desire to know God, God also knows me. While I may be known by only one name, God has many names or no name. I don’t have to prostrate myself or be in a place of worship to call on or lift up the name of the Most High.

May this meditation manual be a blessing to many, and may it be one of many more to follow!

– Reviewed by Rev. Dr. Qiyamah A. Rahman